Samuel Blaser: ‹In truth, we are all waiting›

9.4.-9.5.2015

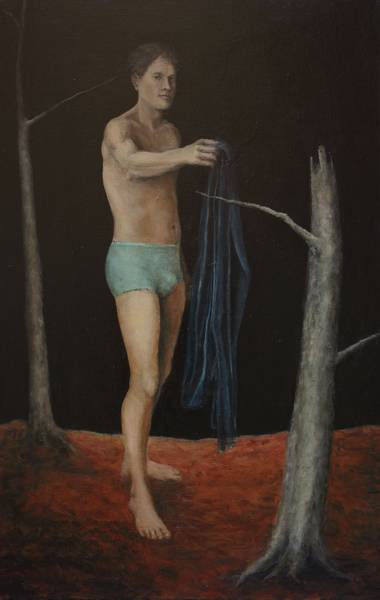

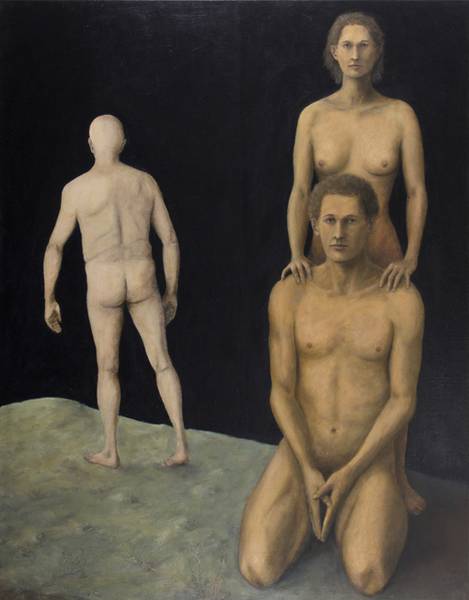

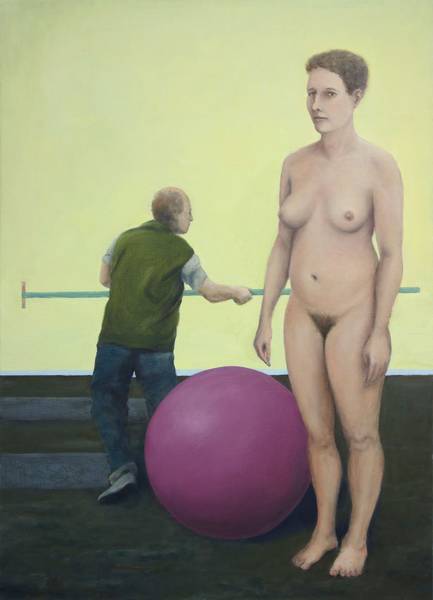

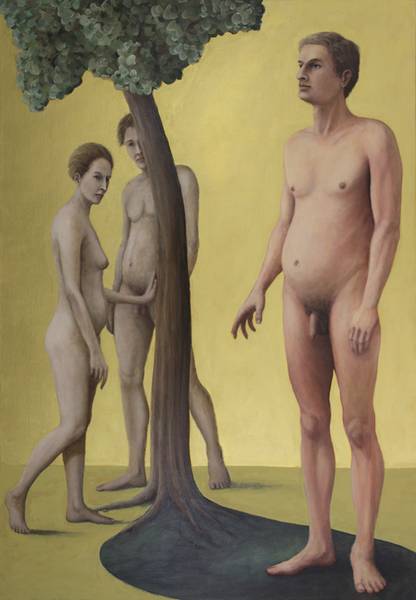

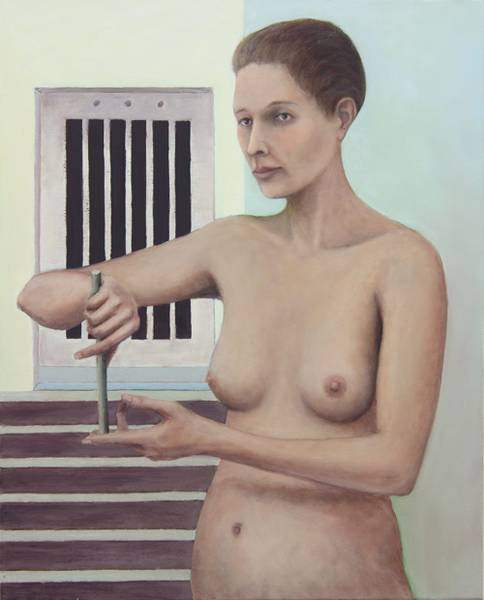

Calmly they are looking at us: naked people, not speaking, touching only slightly if at all. It is notions such as pausing and standing on the side lines that are at the centre of Samuel Blaser’s painterly interest, confronting us with numerous situations that deal with togetherness and communication. Fragments of interaction transcending the depicted figures, they cross over to the beholders, who seem locked in the figures’ gazes. It seems as if the portrayed had been waiting for their audience. And yet, voyeurism is avoided. The viewers are rather participants invited into the picture with no guarantee as to what might happen next. This stepping into the picture extends beyond the usual forms of relationships and traditions, with the artist’s painting style consciously avoiding any categorisation.

Blaser mentions the Old Masters as well as Neue Sachlichkeit’s “magic realism” as references, appropriating their visual language while giving his pictures a distinctly contemporary edge. But his paintings can only be called naturalistic because one can recognise human beings, with hardly any pieces of clothing in this pictures at all. Blaser is mainly interested in the skin, the demarcation of the individual with the outside world, as much in the material as the metaphoric sense. For him depicting and analysing the naked body is tantamount to searching for the human core that sets the individual apart from society as a whole. Last but not least the skin stands for interaction, this most direct of social contacts, also between image and beholder.

Quite in contrast to the bodies’ open demonstration of gender, their heads remain androgynous. By eliminating bold characteristics the artist succeeds in attaining the “idea” of a human being transcending all individual biographical details. In doing so, Blaser adumbrates the various facets of basic questions of existence, encouraging us to reflect not only on social coexistence but also on mortality. Blaser keeps shaping his figures until he himself can learn something from them. They seem to hover in a “centre” exposed to everyone’s gaze and thus denying them a home as it were. This might be the reason why some gazes seem slightly uncanny.

Blaser’s most recent works have grown in format to full-length portraits, a decision that is liberating as much in terms of format as in motif. His paintings – their contents, the artist’s style as well as the medium of painting as such – force the viewers to slow down their eyes, reminding them of the fact that despite all technical progress counterbalances to today’s hectic lifestyle do exist. There are hints of action and stories in these new works, but it is notions such as pause, idleness, waiting, hovering and mirroring – often combined with a subtle, conciliatory sense of humour – that dominate them, bringing up the question if there is any activity at all that can do without waiting. Aren’t we all just waiting?

1) In verità, siamo tutti in attesa, from Cesare Pavese, Racconti, Volume primo, Einaudi, 1960, p.335.